37 38

86

La Lettre

© Photo Researchers, Inc - Alamy

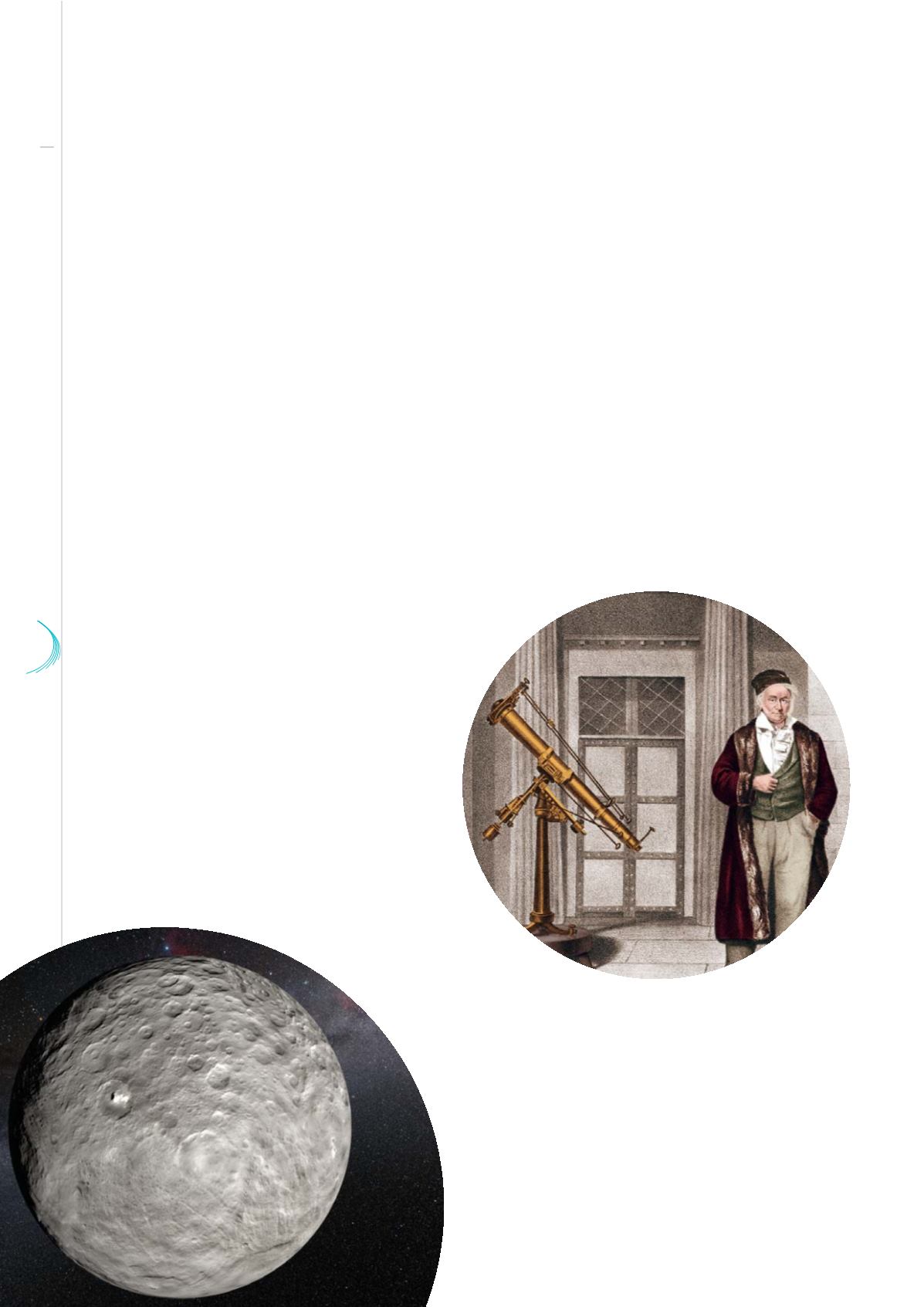

Artist’s view of Ceres

© ESO

Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855)

dear to me: in 1933, Torsten Carleman conducted the first mathematical study on the Boltzmann equation,

describing and predicting the statistical evolution of a gas that experiences unceasing collisions; today, the

mathematical literature on this topic is tens of thousand of pages long.

And mathematicians may now be counted by hundreds of thousand, operating within highly organized

research systems and publishing more than ever – and probably too much – in hundreds of specialized

journals, most of the time in collaboration with others; they gather all over the world, in a relentless

ballet of conferences, symposia and emails. The roles of mathematicians within the industry has been

acknowledged; they have been praised and reviled, and by times called criminals. The time of craft, of

Newton and his colleagues, is far away; and yet their questions are still ours, so as their unremitting desire

to understand and predict the phenomena, with is sometimes fulfilled, other times held in check.

Thus, to the question raised by Newton – Is the solar system stable? – after three hundred and fifty years

of work, the introduction of linear algebra, dynamical systems, probability theory, chaos theory, perturbed

Hamiltonian systems, symplectic schemes and the contributions of such sacred monsters as Laplace,

Lagrange, Poincaré and Kolmogorov – to this question, we may now confidently answer: “

Perhaps

!”

This “perhaps” is nothing we should be ashamed of, as it may be

quantified in probability terms, and as we know it is not

possible to do better: the outcome of the universe is

ruled by a set of probabilities, for lack of an infinite,

unreachable precision. Ultimately, in Newton’s

problem, we are faced with two well-known

conceptual monsters: chance and the infinite.

Prediction and unpredictability are two

themes entwined in each other throughout

this long story, which is not unlike a great

novel, with its share of ironic twists and

turns. Indeed, when Gauss managed to find

the lost orbit of the asteroid Ceres, then to

master Vesta’s, its little sister, the world seemed

most predictible; yet, some two centuries later,

our fellow Jacques Laskar would demonstrate

the perturbing effect Ceres and Vesta has

on the whole solar system, forbidding any

prediction beyond 60 million years. And as for