350

YEARS

OF

SCIENCE

83

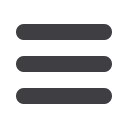

© Photo Researchers, Inc - Alamy

Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695)

presents his pendulum clock to

Louis XIV.

© Archives de l'Académie

Journal of the campaign,

by the abbot Outhier and

Maupertuis, Paris, 1744

© Bibliotheque de l'Institut de France

Pierre Louis Moreau de

Maupertuis (1698-1759)

and the campaign to

Lapland

marked point on a rolling wheel. Indeed, if a

pendulum is constrained by two “cheeks” of

cycloidal shape, then the mass describes

a trajectory that is itself cycloidal; and,

remarkably, the oscillation period will

be rigorously invariant. This enabled

Huygens to build the first mechanical

precision clock, with an error inferior to

one second per hour.

However, the pendulum was far from

saying its last word. In 1673, the astronomer

Jean Richer, who had been recruited as

"élève académicien" in 1666, discovered that his

pendulum ticked a bit slower in Cayenne than in Paris.

Huygens and Newton deduced from this trivial observation that

the Earth, subject to a centrifugal force, is slightly flattened at the poles: a theory that would remain

controversial for half a Century, until a famous measurement campaign in Lapland that the Académie

des Sciences entrusted to

Maupertuis.

Thus, within this pendulum

lie the seeds of two great

scientific epics. One is the

technology

of

precision

clocks, whose most colorful

moment was Harrison’s 1765

chronometer, a real wonder

that would not lose more than

one second per month and

made it possible, through the

calculation of time difference,

to take precise bearings at

sea. The other is the discovery

of the precise shape of the

Earth, whose most dramatic

chapter was the heroic effort

Delambre et Méchain made

on the wake of the French Revolution to measure the Earth and thus provide the world with a truly

universel unit, the metre.