37 38

56

La Lettre

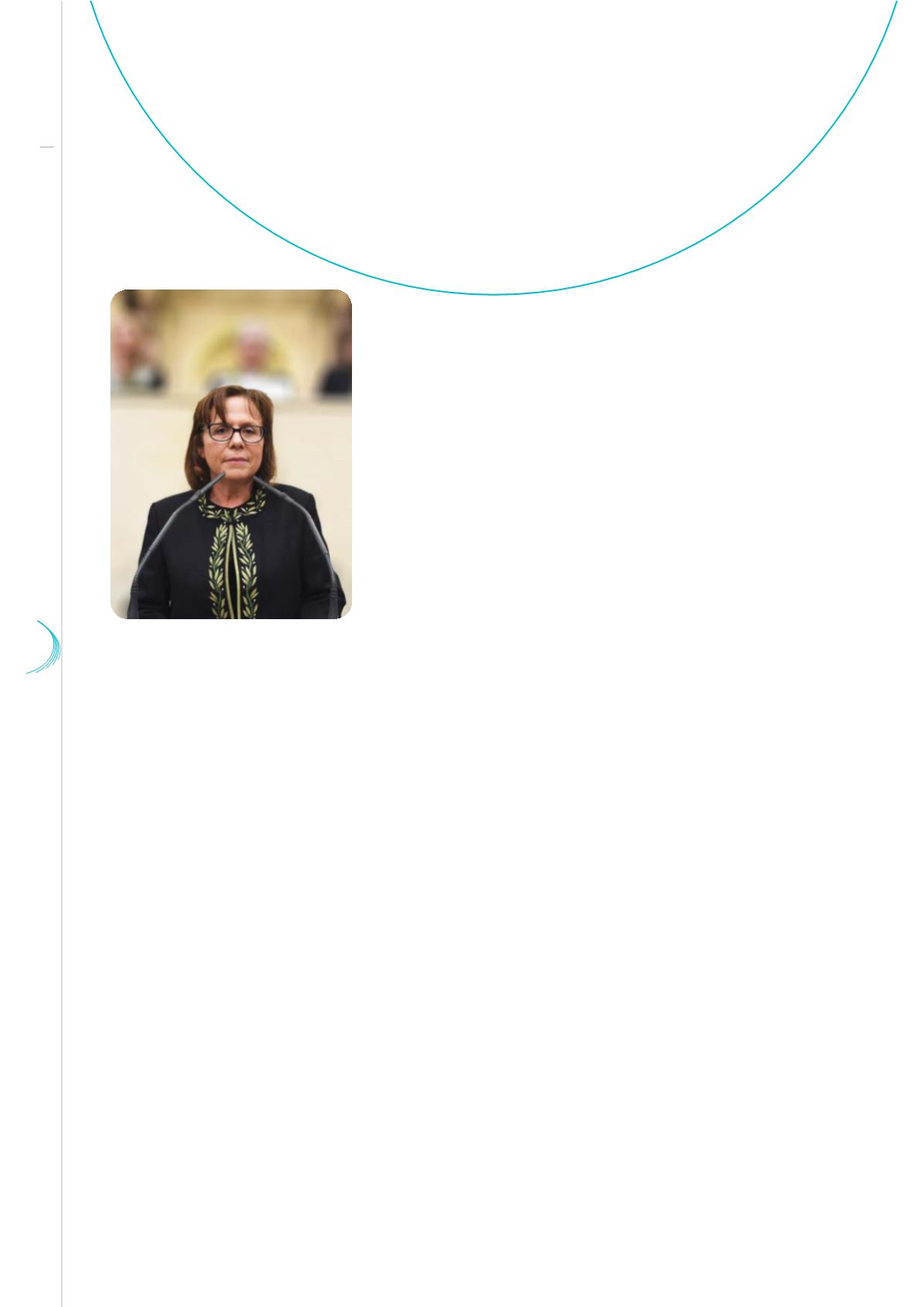

© B.Eymann - Académie des sciences

Anne-Marie Lagrange

Member of the Académie des Sciences, Senior Researcher at

CNRS, Institut de planétologie et d’astrophysique of Grenoble

During the last centuries, our understanding of the world

has considerably changed. Once Earth had lost the

specific status the geocentric system provided it and

once it had been recognised as one of the planets orbiting

the sun, it became possible to examine the formation of

the sun and its planets. Stars, comets, nebulae, galaxies

were observed, identified, catalogued, studied with ever-

increasing precision thanks to progress achieved in spyglasses, telescopes and other instruments,

as well as in physics, chemistry and geology. The observable universe kept on enriching itself and

growing. The possibility that planets were orbiting stars other than the sun – exoplanets – was

considered but it would take until the end of the 20

th

Century for any to be detected and the detailed

study of some known examples to begin.

The place of Earth in the Universe

In the 16

th

and 17

th

Centuries, the theological and philosophical conceptions that, since antiquity (Aristotle,

Ptolemy), had been placing Earth at the center of the world gradually lost ground as progress was being

made in the fields of celestial mechanics and gravitation. The works of Copernicus, then of Kepler, Galileo

and Newton, would now place Earth, and then the planets, in orbit around the sun, moving in accordance

with the universal laws of physics, which thus corroborated the intuition expressed by Aristarchus of

Samos in the 3

rd

Century B.C. Science could now gain its independence from religion – an idea d’Alembert

would cherish. The appetite for science grew, secular structures in which scientists would gather were

created, such as the

Académie des Sciences

in 1666 and, one year later, the

Observatoire de Paris

as the

workplace of the astronomer members of the Roi-Soleil’s Académie.

Planets and exoplanets