37 38

14

La Lettre

© Archives de l'Académie des sciences

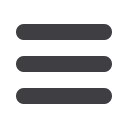

A plate from Charles Coulomb's

First Memoir on Electricity

and Magnetism

(1785)

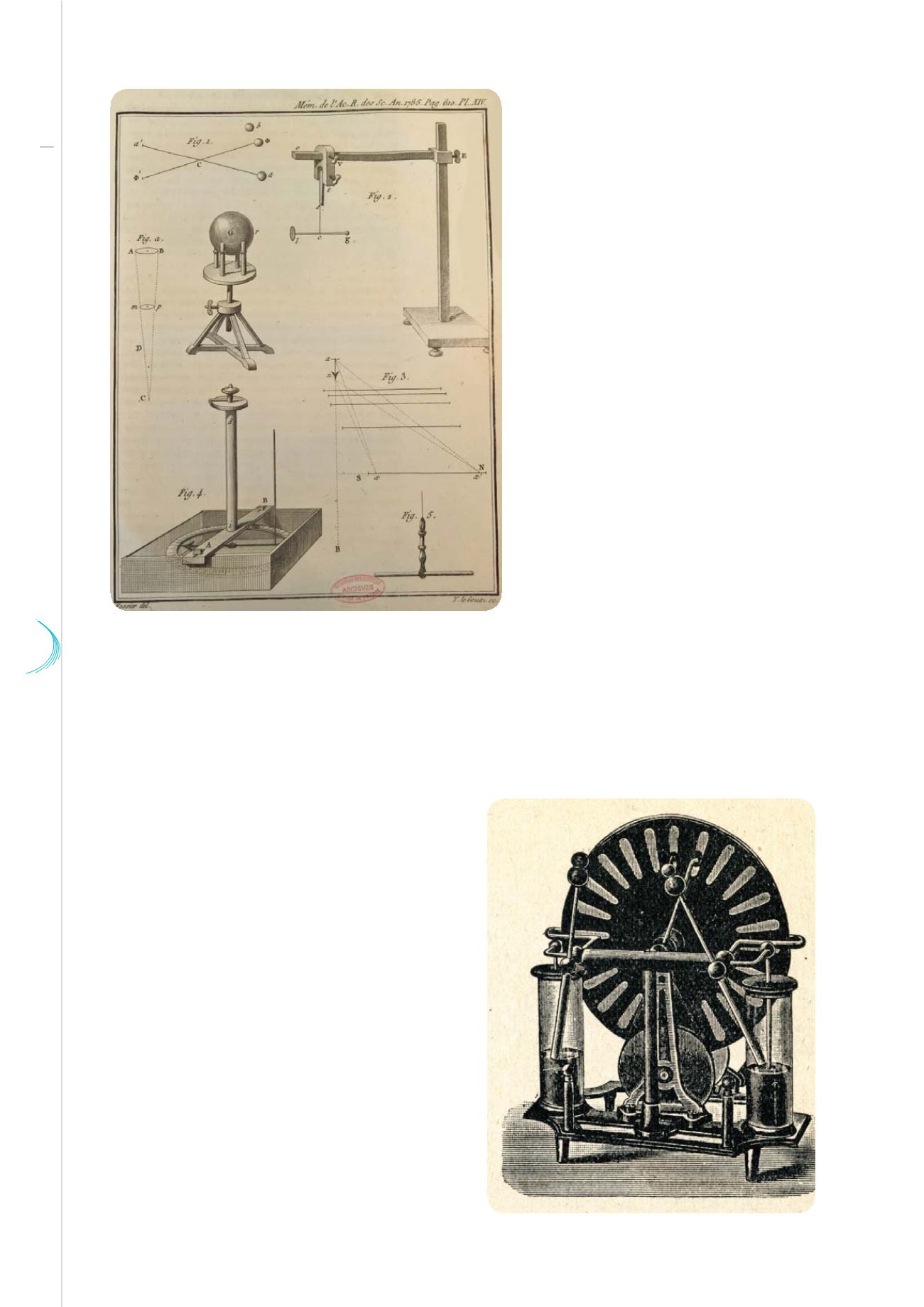

An electrostatic machine

©Juulijs - Fotolia

It is however customary to mention

progress in science. It is because

they are cumulative that sciences

and technologies progress: to add a

contribution to scientific knowledge, one

must know all the links of the chain made

of what was previously acquired. Let’s

take the example of electricity, which

has now become indispensable in our

daily lives. It was discovered very early

in antiquity. The Greek word “electron”

meant “yellow amber”, which was known

for its electrostatic properties. The next

step tobetter understand itwasonly taken

in the early 18

th

Century with Charles

Du Fay who, in the 1730s, dissociated

two kinds of electricity, depending on

whether it came from rubbing glass

or rubbing amber. Soon afterwards,

Benjamin Franklin called them “positive”

and “negative”. Of the same sign, they

repel each other; of opposite signs, they

attract each other. In 1785, Charles

Coulomb presented a memoir at the Académie

des Sciences explaining the force between two

electric charges. Such a force is proportional to

the charges and inversely proportional to the

square of the distance between them. Then came

the electrostatic machines, made to generate

current, which would bring about the birth of

electric circuits. At the end of the 19

th

Century,

J.J. Thomson demonstrated the existence and

role of the electron, which, a few decades later,

would prove to be one of the elementary particles

that make up our universe. In December 1947,

researchers at the Bell Telephone Company, in

the United States, invented the transistor, which

would be the root of electronics. Then, changing

scales to reduce the dimensions of the transistor

in the early 2000s, would emerge the paradigm