37 38

32

La Lettre

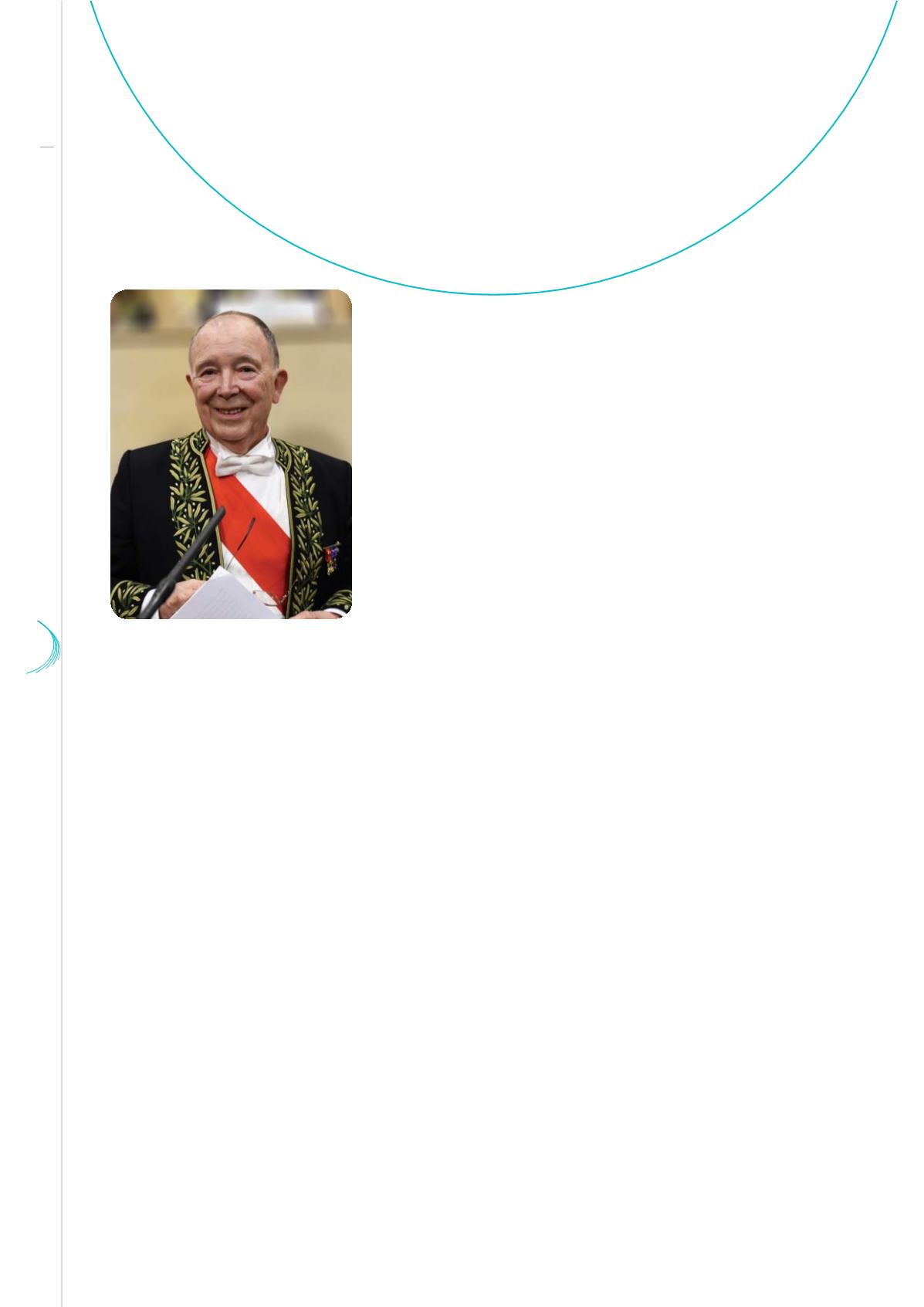

© B.Eymann - Académie des sciences

Jean-Pierre Changeux

Member of the Académie des Sciences, International Faculty at

the University of California, San Diego, Honorary Professor at the

Collège de France and Institut Pasteur

Descartes wrote about 1632 the

Treatise on Man

,

which would only be published after his death, in 1664,

two years before the first session of the Académie des

Sciences was held. Although unfinished, this prophetic

text anticipates, despite the inaccuracies, 350 years of

research on the discovery of human beings and their

brains. From the elementary structures of man’s body –

muscles, nerves “small and big pipes”, and so on – he attempted to establish a causal link between

the anatomy of this “machine” and its physiological functions, one level after the other, up to the

“reasonable soul”, with “its principal seat in the brain”.

Here is the end of Descartes’ treatise: “

In this machine (...) it is not necessary to conceive of (...) any other

principle of movement or life, other than its blood and its spirits which are agitated by the heat of the fire

that burns continuously in its heart, and which is of the same nature as those fires that occur in inanimate

bodies.

” This proposition will be the backbone of my presentation on the successive steps by which our

knowledge on human beings has progressed, from the chemistry of life to the higher functions of the brain.

Step 1: the chemistry of life

In 1661, the Irish Boyle, as a follower to Descartes’ mechanistic philosophy, tried to explain the properties

of matter from atoms he called "corpuscles

"

. He also observed that pumping air from a closed vase

extinguishes the flame of a candle and kills the animals placed inside it.

Lavoisier, the founder of modern chemistry, was interested in combustion. He demonstrated at theAcadémie

des Sciences, on 26 April 1775, that the combustion of charcoal released "fixed" air, which resulted from

On the path to discovering

human beings and their brains